“Cognitive Debt is where you forgo the thinking in order just to get the answers, but have no real idea of why the answers are what they are.”

The idea of Cognitive Debt seems to have struck a chord with folk, in a good way (thank you Neil, Andrew and others who’ve been in touch). So I have pulled it out of the newsletter to give it a home on the blog to point to, and added a couple of other things too.

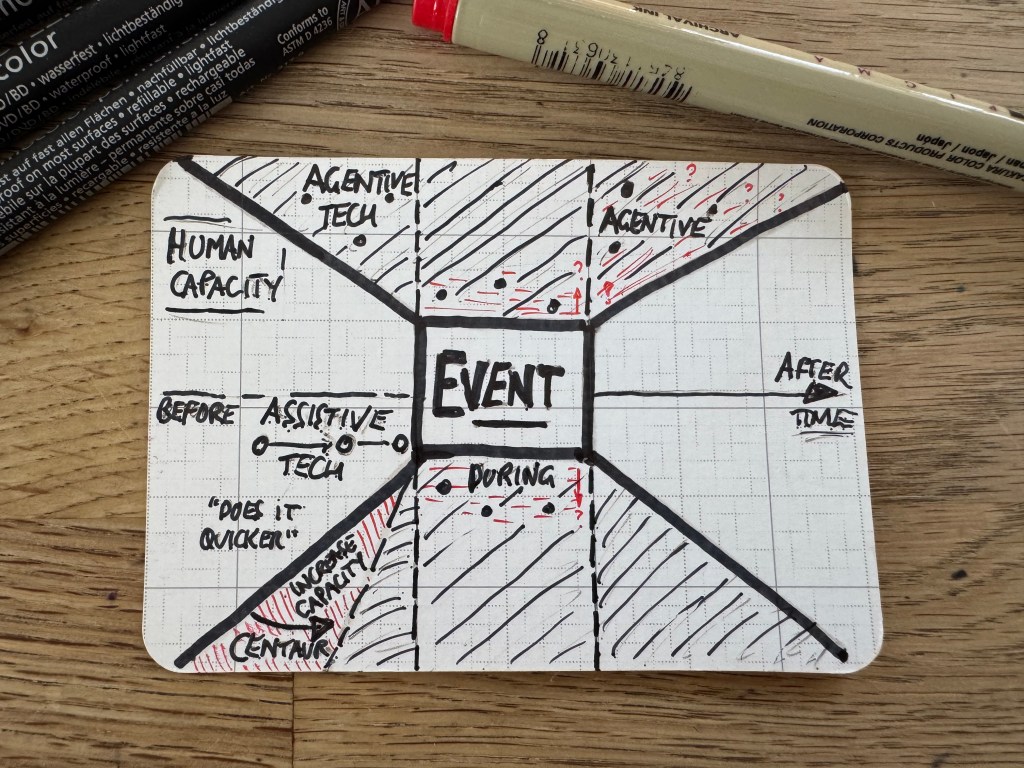

It was part of a longer exploration of a model I’ve been using since 2017 to think about the Before/During/After of events, and where different forms of assistive and agentive technology can play a role in the process.

Directly from the newsletter then:

There are other examples of the Before/During/After framework where we could discuss the efficacy of agentive technology, but rather than spend six thousands word doing that, what I’m beginning to play with is the concept of cognitive debt.

Where technical debt for an organisation is “the implied cost of additional work in the future resulting from choosing an expedient solution over a more robust one”, cognitive debt is where you forgo the thinking in order just to get the answers, but have no real idea of why the answers are what they are.

“Have you really thought about what the question is” etc etc…

Sometimes, this won’t really matter at all. It is low jeopardy if it goes wrong in isolation, and someone will catch it. Yet sometimes, it really will matter a lot.

And the organisation in question will struggle to understand how that answer got in there in the first place...

To expand a bit, then, I want to go back to the Technical Debt idea first.

It is an idea created by Ward Cunningham, about how development teams could make coding decisions that allow them to achieve something in the short term, but only with the understanding that they needed to repay the debt hanging over them. He explains that he was heavily influenced by reading Lakeoff and Johnson’s Metaphors We Live By (oh yes, my friend, me too).

“With borrowed money, you can do something sooner than you might otherwise, but then until you pay back that money you’ll be paying interest. I thought borrowing money was a good idea, I thought that rushing software out the door to get some experience with it was a good idea, but that of course, you would eventually go back and as you learned things about that software you would repay that loan by refactoring the program to reflect your experience as you acquired it.”

You could read more about Technical Debt in this useful primer here, should you wish. Notice that, in the original idea and metaphor, you are always meant to repay the debt. Everyone knows it is a shortcut, and you must revisit the thing you didn’t do before in order to clear your slate.

Perhaps this is a useful measure for Cognitive Debt; are we incurring a debt by not doing the thinking in the present that we will need to demonstrate in the future?

For example, imagine you are asked to recommend the five top markets around the world for a new product launch. Clearly you need to be able to point to the thinking when it goes either very well (as you will want to repeat that process) or very badly (to work out what you’ve missed).

I mean, you would hope nobody would just drop such a thing into ChatGPT and take the answer at face value, but given some of the stories I’ve heard recently I’m beginning to have my doubts.

Also, this post on Bluesky from Andrew Taylor has been living rent free in my head for a week now.

“People have a kind of Gell-Mann amnesia towards LLMs.

They can think “AI is bad at things I am good at and know about, but good at things I can’t judge because I’m bad at them”…”

Sometimes people are asked to do things they don’t know about, and might just type something in the box to get them started…

On the other end of the scale, imagine a repeat customer sends an email complaint that a £10 product never arrived in the mail. With enough information available, and for one-off low-cost cases, of course you would automate this as much as you can. Even as you begin to stack-up hundreds or thousands of such cases, I don’t feel that you are really accruing Cognitive Debt at a significant scale; there are lots of tasks in companies which are fundamentally low-cognition ones.

Of course, there are other problems in deploying AI in the day-to-day low-cognition cases. The opportunities for fraud are present, but hey, fraudsters are always gonna fraud; this is just a different system. Reputational management isn’t great either. Your brand will suffer if you constantly deploy chatbots which can only solve the core 80% of problems, and continually reject edge-case requests. Especially if customers can’t find a human in the system who can help them out.

Perhaps the main difference between Cognitive Debt and Technical Debt is how and where it is accrued, and who decides to accrue it.

In Ward Cunningham’s original articulation, the decision to accrue Technical Debt is a team one. They are responsible for delivering a product in a field they know well, so they can manage the debt accordingly. Even if the budgeting decision to repay that debt lies elsewhere, they can put a fairly persuasive case together on why and when that should happy.

Technical Debt is accrued locally, with high-specificity, and direct accountability.

Whereas, in an age of CEO edicts to be AI first (e.g. Shopify, Duolingo as the latest and most public ones), Cognitive Debt is being forced into all teams in organisations in a big effort to maximise productivity and minimise cost. If you are being told that you have to use certain AI platforms as part of your role, or bespoke ones built for tasks that you used to do yourself (e.g. candidate selection in the hiring process), it it probably quite hard for you to push back, even if you know your field better than the superiors insisting you adopt AI.

Cognitive Debt will increasingly be accrued globally, with low-specificity, and unclear accountability.

I’m going to spend some time this month working through the impactions of this, and I’m already talking to some friends on what we might put together as a result.

In the meantime though, I’ll leave you with this excerpt of an idea from Andrew on how he plans to use the Cognitive Debt idea more immediately.

“Alongside my AI tools and process shortcuts, I’ve now adopted a critical new question to ask. Its proudly scribbled on a post-it note on my screen as I type.

“How large is the cognitive debt that taking this shortcut will accrue?”