Filmmaker Danny Lee on revealing an icon

Our careers include titles and responsibilities that we’re often unable to fully inhabit when we first start in them.

I edited Red Bull’s magazine for eight years, helping it grow from print into a digital offering across social, audio and YouTube. When I began, I was a text-based journalist who had storytelling instinct, but no experience translating that into moving images.

Then Danny Lee entered my life, via friend-of-the-letter Raymond Roker. In the two years we worked together, Lee and his CALICO production studio spun out prize-winning short documentaries on topics as diverse as East Coast surfers, Native American skateboarders, and Pharrell’s BMX passion. I once sent him to Juarez, Mexico in the middle of a drug war to tell the story of a nightclub, of all things.

He wasn’t too thrilled about that last one.

A native of Los Angeles, Lee’s spent most of his career documenting characters at the intersection of culture and society. He’s done brand films and documentaries that aim to not just highlight the contributions of sneaker-heads, athletes, comedians, and artists, but honor them.

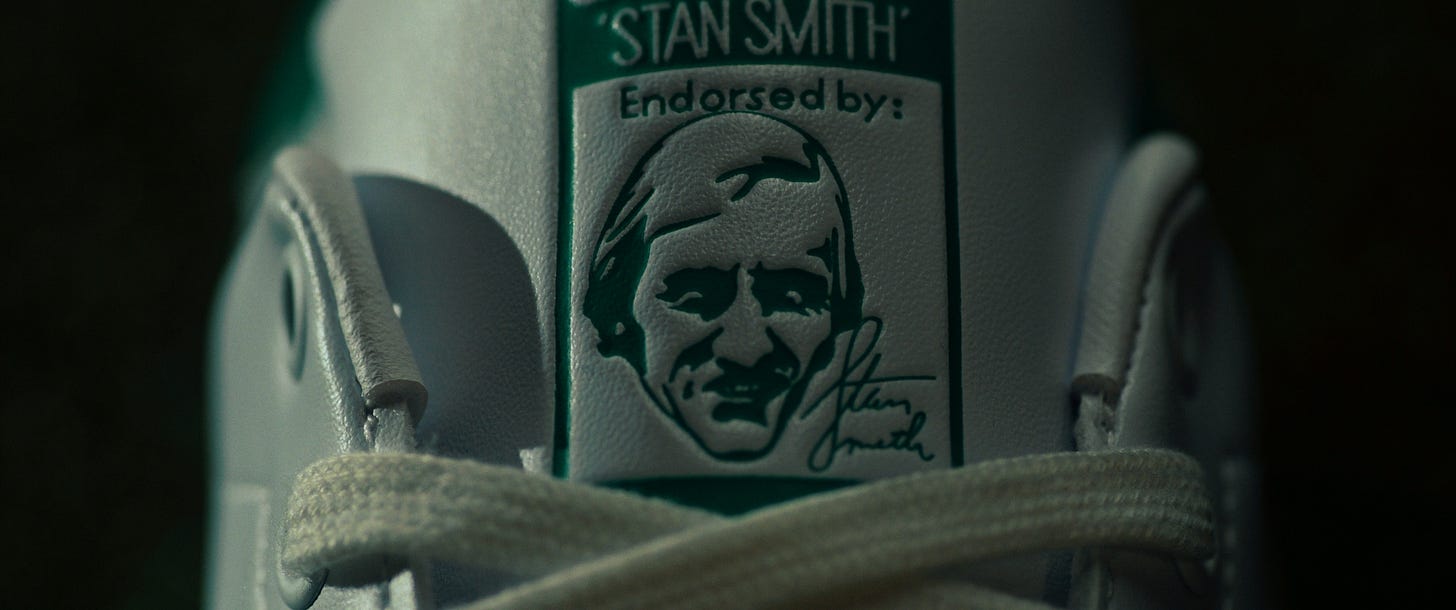

Last year, he released “Who is Stan Smith?” on Hulu and Disney+, together with LeBron James’ entertainment company Fulwell (formerly Springhill Entertainment). Artfully shot, blending historical footage and current interviews with everyone from Pharrell to Darryl “DMC” McDaniels, the documentary for the first time pulls back the curtain on the man behind the iconic Adidas sneaker. What emerges is something more than a shoe or brand story, but the narrative of a man who has used his unique blend of talent, compassion and humanity, to uplift others. He, and this lovingly crafted piece about him, feels like a balm for these times. I asked Danny to talk about what he learned in making it.

So I suppose it makes sense to start with the question: Why Stan Smith?

DANNY LEE: I’ve always been really fascinated with all things culture. As a filmmaker, I’ve always fashioned myself as wanting to be a custodian of things in culture, so that the history is properly encapsulated and relayed to future generations for posterity. Some of it was out of duty, some of it was genuine interest because I had always heard the name but never knew the story behind it.

In fact, I wasn’t sure if Stan was still alive. Even when I was in high school 20-plus years ago, he was always this mythical name and mythical figure in American sports culture, sort of the first name I can remember, athlete-wise, that crossed over into pop culture.

What did you understand about Stan Smith before you started digging in?

I just knew that it was a clean, elegant shoe that was aspirational at the time. In high school I was rocking shell toes and suede Pumas. I was a hip-hop kid, so I wasn’t even rocking Jordans as much. I was into what old school B-boys would wear, and Stan was part of that family, although more on the Beastie Boys side.

My tennis knowledge at the time was Andre Agassi and Michael Chang. I was into that whole era of early ‘90s infrared colors. But I wasn’t a huge tennis head. I was a hip-hop kid.

How did your perception change in the making of it?

Immensely. It coincided with me finding tennis during the pandemic. I started this project in 2021 and, like most people, we were looking for ways to exercise and get out. I would naturally default to basketball, but I’d go to the courts and see the nets all tied up. Then I’d look over and see the tennis courts wide open. That’s literally why I started playing tennis.

What I learned about Stan through the process was very organic. As any filmmaker should in the documentary format, you need to have your eyes wide open, your heart open, ready to be curious and learn. As I took a deep dive into all things Stan — anything I could find on YouTube, reading his book, or deep research with my team — I discovered there was a lot to him.

How willing a participant was he?

Like with any of these docs that feature a high-profile celebrity, you meet multiple directors. He and I were able to really connect well … That’s more a testament to Stan than me. Stan’s really easy to get along with. We built trust and talked a lot. He opened up immediately.

I think that was easy for him because he didn’t have any big scandal in his life. The biggest challenge wasn’t access, it was more about taking a life well-lived that doesn’t have a lot of tension in his core life and turning that into a proper film, because any film builds off tension.

So how did you find the narrative arc?

We had to find tension in the stories around him and the people he intersected with and the world events happening around him. His tennis journey took him through probably the most tumultuous time in American history, like civil rights, Vietnam, and then internationally through apartheid.

You dive into his relationship with a young, black South African he rescued from the apartheid government’s clutches. What did that reveal about Smith’s broader impact?

I think allyship is obviously a big theme running throughout, whether racial or class-based. But it’s also this idea that he’s so humble, I don’t think he understands his impact to the full degree.

What he did learn from all this is how much (African-American tennis legend) Arthur Ashe impacted his life. He says it on screen: he harbors some regrets that he didn’t maybe do enough for Arthur. Anyone can draw a straight line from that sentiment to why he helped Mark Mathabane. I think he felt like, “Why didn’t I do enough for Arthur and his causes? Let me make up for that with Mark in some ways.”

What about his understanding of his impact in sneaker culture?

He’s loyal to Adidas to the bone, and he knows his impact on sneaker culture. I don’t think he reads Complex or Hypebeast or cares that much, but he knows. He’s an interesting dude because he’s connected to all these worlds. There’s this quality to him that just attracts energy and culture and praise.

You mentioned his loyalty to Adidas — is that why the partnership has endured so long?

We’re living in times of opportunism where everyone is looking for the next best deal and not really caring about staying on the same team or staying in line with a certain brand. Athletes from that era were just cut from a different cloth.

Stan is emblematic of someone who rested on this virtue of loyalty, regardless. His first agent, Donald Dell, is still his agent. They don’t have a signed contract with each other.

I think he recognized how much Adidas took care of him, and how much they amplified him. He wasn’t the winningest player ever. He only won one Wimbledon, and a few Grand Slams.

Why do you think Adidas stayed with him ?

It’s like the Jordan for them, right? It has that same legacy … Tennis is only growing bigger and bigger as a culture, becoming more accessible.

I think they’d be foolish to abandon their alignment with Stan. These sneakers live or die on heritage in a lot of ways. They also sometimes live or die off the right groups embracing them at the right time, but then they run the risk of being abandoned by those groups.

Adidas also had a high tolerance level for that. I mean, I’ve always seen Adidas as a brand that truly has been interwoven into cultural milestones: the birth of hip-hop, terrace and football culture in Europe. I associate them with heritage.

Why did you give the film the title you did?

He’s sort of this Paul Bunyan-type character where you know the myth but don’t know where it comes from or why we care … It was a mystery.

The unfurling of the story is answering the question … and ultimately my intention was to point the answer back to yourself.

Stan Smith is the everyman. He’s all of us. Jam Master Jay (of Run DMC) sort of says it in this poetic way at the end. Stan proved that in his actions: he worked for and fought for every other tennis player, big or small, in forming the ATP (Association of Tennis Professionals) and unionizing tennis. He fought for folks of other races because he believed in our common humanity.

It was a complicated story because nothing was very clear until I went through the process.

The lack of high stakes or obvious tension is quite rare in documentaries these days. Were you concerned about that?

I knew that didn’t exist in this story. There’s a place for that stuff, it gets people to watch and talk. It just didn’t exist in this story.

I took inventory of my projects recently and I’m like … I realized I’m sort of a sap. I like a happy ending. I want to have some thread of inspiration so people can feel good. Because we’re surrounded by so much nonsense that I wanted to make something really honest and meaningful.

When you’re dealing with someone like Stan Smith, you can’t whiff. This is something that has to live on forever. We’ve gotten an incredible response. I have random people reaching out via email saying they were really moved, that they never knew this much about him, randoms emailing me from watching it on the plane.

That, for me, is what it’s really all about. It sounds cliché, but it really is. We don’t get rich off docs, that’s for sure. I get off on having these time capsules.

That’s a nice way of putting it. You talked at the beginning about seeing yourself as a custodian of culture. Why is that important to you?

I’m serving the culture at large. I get frustrated when I see a film, a doc, a commercial — whatever it may be — that’s treating cultural touchstones without care.

Hip-hop was very meaningful to me. It’s not just something I grew up with, but it was a bridge between myself and people from other walks of life. We could all agree that we love this one song. We would share a dub, or a mixtape with each other. For me, it became a cultural bridge. Sometimes I felt like a tokenized Asian kid, but then I could connect on hip-hop.

Culture has been such a sidecar of my life, and therefore I want to make sure the stories are told properly. I was pushing stories of culture in the 2000s as an early filmmaker and no one wanted to listen. Now it’s become part of pop culture, and a lot of people are just exploiting it.

I just want to make sure it’s done right. I want to make sure other filmmakers do it right. That’s not to say I want to be a gatekeeper. I just care a lot … Culture is a window to humanity. It’s a way to organize people and common values. Culture is a way into our psychology, our humanity, and that’s what gets me really excited.

Stan checked off all those boxes.

“He’s the everyday man that represents the real power in all of us.”

– Darryl McDaniels (Run DMC)

Are you still in touch with him?

Absolutely. He sends me Christmas cards, we talk all the time. He set me up at the US Open this past year—Arthur Ashe’s seats, third row, (Aryna) Sabalenka on opening day, smashing a ball.

I love that man. I know it’s going to be very hard to match a relationship like that. He was so welcoming. I don’t want to sound hagiographic, but it was so obvious when I went to his home. All of his children, all of his grandkids, they all have his DNA. Not just literally, but the way they were welcoming and warm. It’s really remarkable.

It’s not an act. With 98 percent of celebrities, it’s an act. I saw intimately how his actions have spread across to all the people he’s come in contact with, from Mark Mathabane to his own children, to people who just watch the story.

I think he does deserve his flowers. He is a really good human and a good model for what we all need to be.